Establishing a Structured Mentoring Relationship By Carl A. Moore Jr.

Most people agree that good mentoring is essential to success. Whether the focus is on

academic, athletic, or professional pursuits, a mentor helps the mentee evaluate goals,

establish plans, and monitor progress. Since the impact of mentoring is substantial, why do

fewer than one-quarter of students have a mentor? The answers are numerous, but one that

stands out is that many well-intentioned people don't know how to establish and maintain a

structured mentoring relationship. And because many are unsure of what makes mentoring

effective, mentoring relationships can devolve into ordinary advisor-advisee relationships or

even friendships. Whether you are a would-be mentor, mentee, or administrator establishing a

broad mentoring program, this guide will explain how to foster structured and effective

mentoring.

STEP 1: Discovering Needs

A mentee's lack of clarity on their goals or needed improvements makes it harder to select a

mentor and more difficult for a chosen mentor to know where to focus the mentoring. Therefore,

the first step in establishing a new mentoring relationship is self-evaluation. The suggested tool

is called the individual development plan (IDP). Like a traditional personality test, the IPD asks

the mentee to look within themself, consider their short, mid, and long-term goals, and which

skills will be needed to accomplish them.

The IDP better positions the mentee to choose an appropriate mentor. If the mentee already has

a mentor but has not completed an IDP, the mentor should suggest completing one. In either

case, the mentor should review the IDP results to understand the mentee's needs better.

Below are links to some popular IDPs.

Dr. C Gita Bosch IDP for Undergraduate Students shows how to create an IDP for

undergraduates, complete with examples. Dr. Bosch's IDP includes a goals worksheet, a

self-assessment, and a list of traditional core competencies for undergraduate students.

myIDP from ScienceCareers.org is a long-form online survey of goals and areas for

improvement according to STEM discipline. It is general enough for use by

undergraduates though it was developed for Ph.D. students and postdocs.

The University of Wisconsin-Madison Self-Assessment questionnaire was established

for graduate students. It is a flexible tool that is appropriate for students of any discipline.

UC San Diego Standard IDP Form for Graduate Students is meant to be completed by

both the mentor and the mentee. It uses a table format to organize a list of skills to be

assessed, action steps, and target completion dates.

Mentors should also evaluate themselves using a reverse IDP throughout the mentoring

relationship. For this, consider The Mentor Mirror by Dr. Renetta Tull. It flips the standard

mentee IDP questions around to help the mentor see if they are providing the mentoring

experience their mentee needs. Finally, note that the IDP is not a once-and-done process. Both

mentor and mentee should return to it yearly to evaluate progress and update goals.

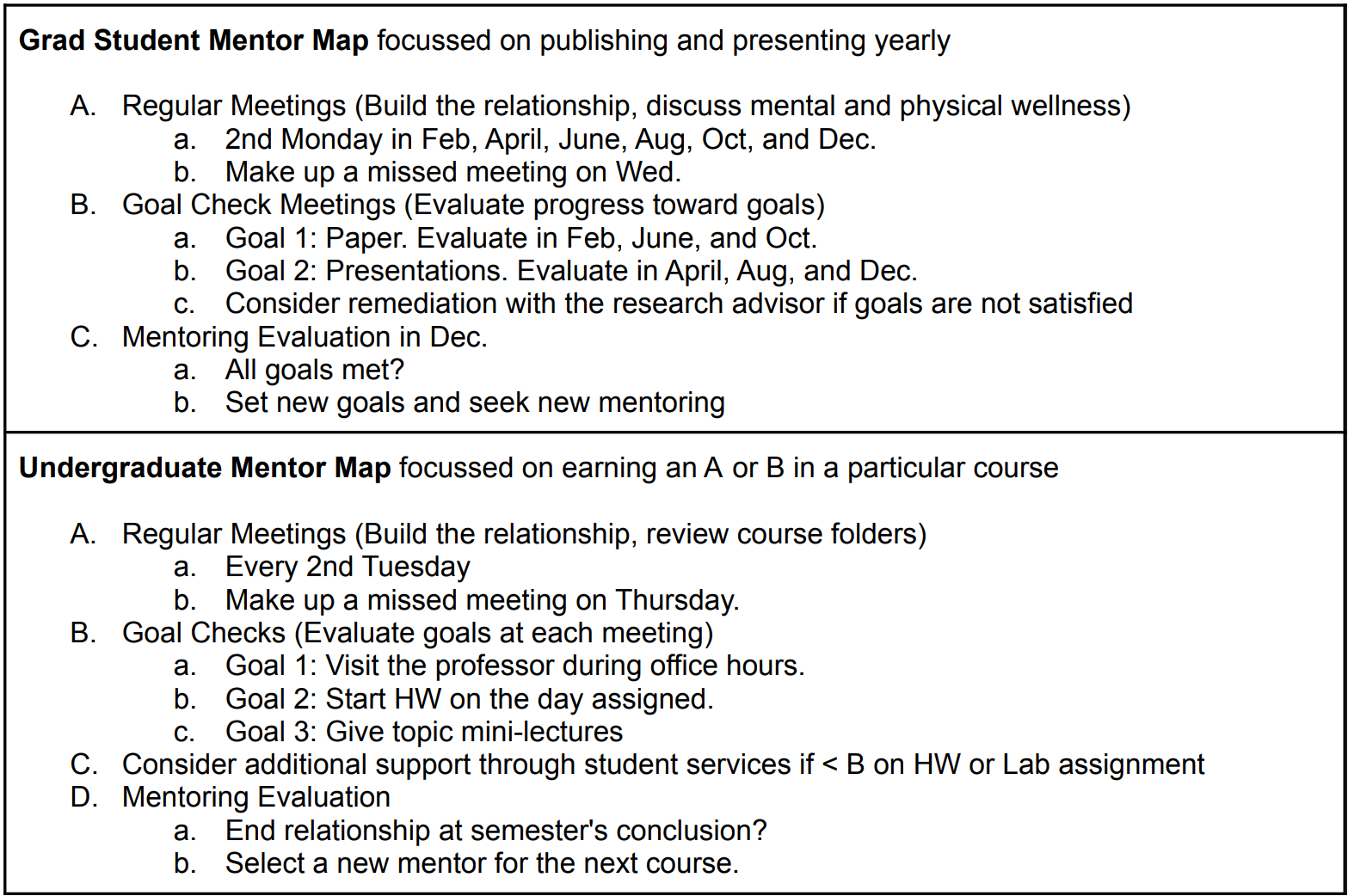

STEP 3: Managing the Mentoring Relationship

After personal introspection and establishing expectations, it is time to manage the mentoring

relationship. For example, participants should address how often they will meet, the purpose of

the meetings, and how to evaluate progress. The Mentor Map is a tool designed to address

these requirements and keep the mentoring relationship on track. Think of the mentor map as a

set of post-it notes on a calendar reminding you when to meet and how to evaluate progress

and goal completion. Below, Table 1 contains two example mentor maps. The map on the left is

for a graduate student who is intent on publishing and presenting her work this year, and the

map on the right is for an undergraduate who is determined to earn no less than a B in one of

his required courses.

Besides satisfying the goal of writing a paper and presenting her research, the graduate student

wants the mentor's help monitoring her mental and physical wellness. Each map lists regular

meetings and goal-check meetings. The map specifies meeting types and backup dates if they

miss a session. For the graduate student, the mentor and mentee will discuss wellness issues

at every meeting and the progress toward the goals at every other meeting. The undergraduate

course will last only a semester, so the mentor and mentee decided to review the mentee's

course folder and goals progress weekly.

A mentor map should also include what to do for missed goals. Regardless of the remediation,

including an option for a missed goal encourages both parties to take action. It is also important

to specify when to evaluate the mentoring relationship. At the start, both parties should discuss

the goals of the relationship and what should happen when these goals are satisfied. Perhaps

they should identify new goals, end the mentoring relationship, and start a new one. Whatever

the case, the mentor map will remind you to consider these possibilities.

STEP 4: Keeping Everything Organized

The Mentoring Plan is the final step for administrators to establish a broader mentoring

program. The mentoring plan includes the tools and philosophy that guide the mentoring

program for a larger group of mentors and mentees. It should set the tone without overly

constraining and be unique because every institution is different.

For starters, a mentoring plan should include the standard tools like the IDP and any others you

feel will benefit your participants. It will be helpful to gather example documents for the

mentorship compacts and mentor maps, presentations on the benefits of mentoring, and

anything else that supports the vision of your mentoring program. There may be other people in

similar institutions working on mentoring programs. Please get to know them and share best

practices. The most important thing to remember is that mentoring is about relationships, so

whatever you do, encourage relationship-building between yourself and all of the participants in

your program.

Finally, structured mentoring may sound very rigid, but every good mentoring program must be

flexible to work with a wide diversity of participants. So, use this guide, but deviate often and

create your tools to satisfy the needs of your participants. If you need help, reach out. There are

a lot of us who would be happy to assist you.