Cryogenic Helium Intro

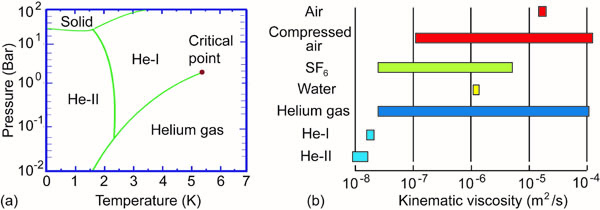

Cryogenic helium-4 has long been recognized as an useful working fluid for turbulence research and for cooling scientific and industrial facilities. As shown in Fig. 1(a), helium-4 exhibits three fluid phases: a gas phase, a normal liquid phase (He-I), and a superfluid phase (He-II). Both gaseous helium and He-I behave as classical viscous fluids governed by the Navier–Stokes equations. In contrast, He-II is a quantum liquid described by the two-fluid model, consisting of two interpenetrating components: a viscous normal-fluid component, associated with thermal excitations, and an inviscid superfluid component corresponding to the condensate. The normal-fluid fraction decreases continuously from unity at the superfluid transition temperature (about 2.17K) to zero as the temperature approaches absolute zero.

Being classical fluids, gaseous helium and He I possess several unique properties that distinguish them from most other fluid materials. In particular, the critical point of helium-4 (Pc = 2.24 bar, Tc = 5.19 K) is readily accessible. By adjusting the pressure and temperature in the vicinity of this critical point, the helium density, and hence its kinematic viscosity, can be varied over a wide range, as shown in Fig. 1(b). This exceptional tunability enables the generation of natural convection flows in helium with extremely high Rayleigh numbers (Ra). Studying the scaling laws of flow parameters at large Ra, where turbulent convection sets in, is of both theoretical and practical significance. Moreover, close to its critical point, helium-4 not only supports high-Ra flows but also offers an unparalleled tuning range spanning twelve decades in Ra, making laboratory studies of oceanic convection and atmospheric circulation possible.

Figure 1: (a) Phase diagram of helium-4; (b) Range of kinematic viscosity of various working fluids.

The hydrodynamics of He II is strongly influenced by quantum effects. For example, rotational motion of the superfluid component can occur only through the formation of topological defects in the form of quantized vortex lines. These vortex lines have identical cores with a radius of about 1 Å, and each carries a single quantum of circulation, κ = h/m4, where h is Planck’s constant and m4 is the mass of a 4He atom. Turbulence in the superfluid therefore manifests as an irregular tangle of vortex lines, known as quantum turbulence. The normal-fluid component, by contrast, behaves more like a classical fluid. However, a mutual-friction force between the two components, arising from the scattering of thermal excitations by vortex lines, can significantly influence the dynamics of both fluids. In addition, He II supports the most efficient heat-transfer mechanism, known as thermal counterflow, and enables the generation of flows with extremely high Reynolds numbers (Re) for turbulence studies due to its exceptionally small kinematic viscosity.

Despite the great potential of helium-4, a grand challenge in this field is the lack of reliable, quantitative flow-measurement tools. Conventional single-point diagnostics, such as Pitot pressure tubes and hot-wire anemometers, offer limited spatial resolution, and in He II their responses can be influenced by the motion of both fluid components. When the normal fluid and superfluid have different velocity fields, data interpretation becomes particularly challenging. A more desirable approach for probing flow dynamics is therefore direct flow visualization. In the past, several laboratories, including ours, employed micron-sized solid particles as tracers and developed particle image velocimetry (PIV) and particle tracking velocimetry (PTV) techniques for He II. Owing to their relatively large size, these micron-sized tracers can readily become trapped on quantized vortices, where their large binding energy to vortex cores enables the visualization of vortex-line structures. However, the heating associated with tracer injection can induce significant disturbances in the helium. More importantly, the strong interactions between the tracers, the viscous normal fluid, and the quantized vortices render tracer motion difficult to interpret in realistic turbulent flows.

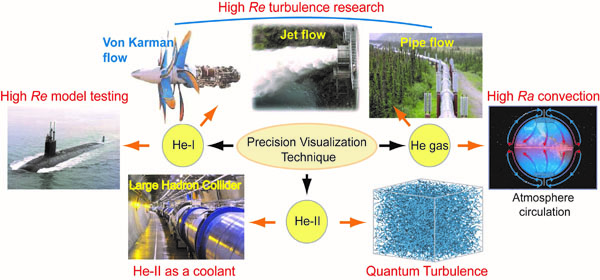

One direction of our research focuses on exploring the rich and fascinating quantum hydrodynamics of He II through the development of advanced flow-visualization techniques. In particular, we have conducted a series of experiments that demonstrate the superior capabilities of metastable He2* molecular tracers. These tracers unambiguously track the normal-fluid motion above 1 K and enable direct imaging of quantized vortices in the pure superfluid regime below 0.5 K. Significant progress has been made in establishing high-precision flow-visualization methods based on He2* tracers. These techniques are expected to open new avenues for quantitative studies of high-Reynolds-number flows in cryogenic helium-4, as well as for fundamental investigations of quantum hydrodynamics in He II. A broad range of scientific and technological applications can benefit from these advances, as illustrated in Fig. 2.